“Witte is one of those poets who doesn’t suffer from being a modern, who is able to contain, under the same hat, what is rich and full and abundant (what we said we lost) and what is nervous and new and wild.” —Gerald Stern

“Witte’s poems are carried on a quiet intense voice talking about a satisfying range of concerns. His poems are of connection: the pains, the problems, the unravellings, the small successes. His landscapes have people in them working, farming, quarrying, pumping gas; they are economic as well as aesthetic entities, and their history works in the present concretely. His family poems embody the same urgencies of history and connection. —Marge Piercy

“John Witte puts his poems together with a certain rough efficiency, and he knows how to finish them off. “Catfish Reunion,” one of several poems in this collection that deal with a world that is passing, turns on a moment in which Witte imagines that he will join the fish he once tried to catch, “slip out over the long cloudy bottoms,” and with them “thread past / jangling hooks and lures” as they leave behind that part of the river polluted by factory acid. If he has been influenced here by Elizabeth Bishop’s enchanting poem, “The Riverman,” one can hardly disapprove, and in any case that passage launches a fine last stanza: “Soon we’ll be choked back / to the headwaters / where there’s nothing left / but to climb up into the rain.”

“It isn’t much. It isn’t anything / gold beaten into fragile figurines, only / clear,” he hopes in one poem, and indeed his best work is that in which clarity takes precedence. Take “The Crotch Island Quarry, Maine.” The longest poem in the book, it is an elegy for both the granite used in our public monuments before glass and steel replaced it and the rugged yet perhaps more congenial and heroic period that produced it. It begins, as it happens, with virtually its only figurative touch, a graceful one: “Deer Island Pink, for seventy years, roses / floated across Jericho Bay, / gaining Stonington.” The simile not only makes the name of the granite and the obvious verb seem perfect choices but also lifts the huge blocks of stone into a different, more romantic world. It establishes a point of view, that is, which the reportage in the rest of the poem both challenges and justifies – for in the end Witte’s realism ballasts his nostalgia rather than sinking it. Here we have not only people like Mary Prescott’s father, who cracked his head so badly in a fall into the pit that “All he could taste was peas,” but also the “round dinner pails” their wives packed for the quarrymen:

At the bottom there was a well for tea,

over that a section for soup,

then a place for sandwiches,

and on top room for a large pie.

set the pail over a fire

and the tea warmed your whole meal.

One admires Witte’s restraint, his refusal to do anything fancy with the image. And of course he’s right – the charm of the object is its homely economy. He keeps himself in the background at the end of the poem:

The stones appear fleshy.

Feldspars, the sorrel flecks

they call “horses in the granite”

catch your eye. Kennedy’s memorial

has them. A summer rainstorm and the stone

is skittish with horses.

It would be hard to overpraise this kind of writing in a first book. Kennedy’s memorial was the last structure to use granite quarried on the island, so Witte lets it become the stone’s memorial for itself. At the same time, by virtue of specific information, folk metaphor, and simple observation, the stone comes to life for a moment and brings with it a bit of history.” —Stephen Yenser, The Yale Review

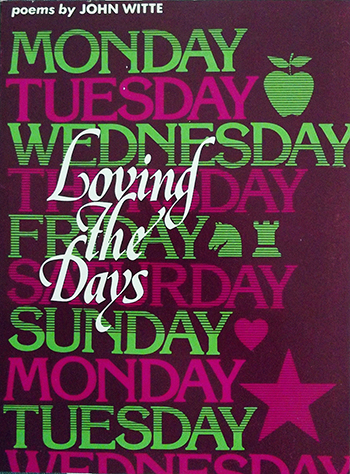

Loving the Days