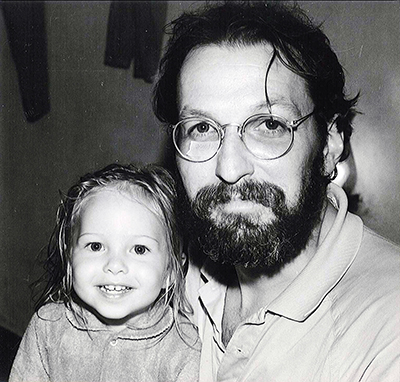

photo: Deb Casey

Some of your poems seem to be meditations on moments of human frailty or failing, like going the wrong way on a one-way street, getting stitches, or giving blood. Others explore interactions between humans and animals, such as hitting an animal with a car or catching a seagull with a fishing hook. And still others focus on objects of the everyday.

I think of the poem as a sort of prism, an arrangement of words that refracts the light and reveals its hidden colors. Animals make particularly good subjects. They are at home in the world, and so we look on them with wonder, even envy. The way we destroy them so heedlessly can only impoverish us further, and compound our grief. John Berger wisely observed that we are haunted by animal extinctions because they anticipate, and very likely predict, our own. So the animals in my poems – and there are quite a number of them – act as prisms to refract the human, and reveal it for what it is.

And yet, your children make appearances in your poems . . .

They are my moorings . . . and my meaning.

One of the first things readers notice about your poems is that they are structured, yet also generally free of punctuation. What role does this structure play in the expression of the subject matter?

It may be that our poetry lacks an audience not because it is too difficult, as is often the charge, but because it fails to describe our lives. Poetry, anchored to words and their fixed definitions, is the most conservative of artforms. While painting and jazz and dance have, for the better part of a century reflected the accelerated, machine-driven cadences of life as it is actually lived, poetry has clung to its pastoral, contemplative, conventions. My poems are structured, as you suggest, hopefully achieving some of the cohesion and snap of a sonnet, but also, in their long lines especially, conveying the chaotic rush of our lives. Maybe I can best illustrate this with a quote. Tercets, for example, might unfold something like this, from “Stitches”:

Threading the needle

is it you at work in the nimbus

of pain stitching my thumb folding the ragged flap of flesh

sewing a glove

a difficult seam grandfather nothing

but a name a needleman in the rag trade dragged into an eddy

of time I turn

away the wound swabbed and numbed

the long thread drawn through tugged tied and snipped…

and so forth. Above all, I’m after the kind of forward plunge we find on the front page of the newspaper every day. Not surprisingly, there’s a lot of stammering and staggering in these poems. One editor called them “whiplash triplets.”

When did you first begin writing poetry? You mentioned that you applied to graduate programs in both creative writing and anthropology. What confirmed your decision to pursue creative writing?

A friend put this well, when asked the same question. He said, “I had an empty place inside. And it didn’t seem like a PhD was going to fill it.” After college I worked for six years as a carpenter, making a living, learning the trade, and devoting a part of every day – as I’ve done ever since – to writing. I began to read everything I could lay my hands on. Those were difficult, glorious years, dedicated to finding myself and my voice.

What are your impressions of the direction new writers of poetry and fiction are taking in their work? What advice would you give to young writers who are just starting out?

Eudora Welty said, “Everyone wants to be a writer, but no one wants to write.” I wish I encountered more often in young writers a sense of serious vocation. An obvious danger of writing programs is that students naturally measure their writing against their peers, or their instructors, rather than the masters, like Bishop, Lowell and Plath, and more recently, Anne Carson and Carl Phillips.

I always encourage young writers to read omnivorously. I love the moment in Walden when Thoreau says that reading the newspaper his fish was wrapped in satisfied the same need as reading the Iliad. I would also encourage a young writer to look to other artforms for inspiration. Painters, dancers and musicians are miles ahead of us. They are already there, doing the important work. Personally, I’ve learned more of value from the frenzied canvases of Gerhard Richter, and the relentless rhythms of Philip Glass, than from most of what I read.

Finally, the young author is often muddled by ego, and mistakenly thinks the writing is about him- or herself. But our object is to bring a moment of clarity, however brief, to the reader’s life. The poem or story originates in the self, of course, but is a gift freely given.