THE SOLOIST

STITCHES

FLIES

AS IF

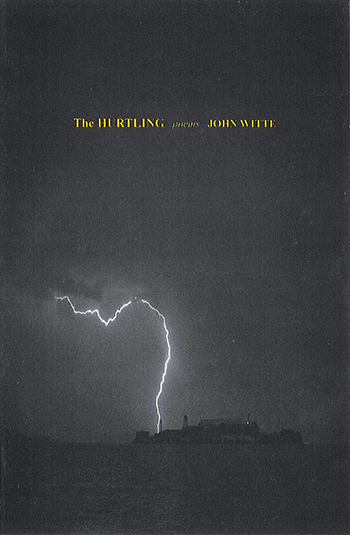

“In The Hurtling, John Witte has invented a new form to be his signature and along with it a language of his own. Thrilling and reckless in their speed, too urgent for conventional punctuation, Witte’s lines hurtle us through ordinary experiences – giving blood, seeing a car head the wrong way down a one-way street – as if these were the matters of life and death that they in fact are.” —Lucia Perillo

“Fierce, controlled, inventive, forward-rushing, refusing punctuation to make free with syntax, John Witte’s cycle of severely unrepetitive three-line-stanza poems left me with endless questions and a durable satisfaction. There are poems here – “As If” is one – which I will never forget.” —Ursula Le Guin

“The Soloist,” the first poem in John Witte’s new collection, describes a musician and the movement of his bow – how the opening phrase rises and breaks through him, how he labors bearing the weight of memory and longing, how his face appears through “this pushing and hurting this bringing forth.” This act of pushing and bringing forth – the act of creating – mirrors the force of the poems in this book. In “The Tide,” the speaker’s daughter compares the dying goat she cares for to a tide going out. The speaker thinks no:

it’s like a tide coming in

the ocean slipping higher clasping making us run the sand

mushy underfoot

swabbing the shore gathering back

the bits of flesh there’s no stopping it no telling it no.

—Gina Meyers, Octopus Magazine

“Although they do not employ meter or rhythm, Witte’s poems in The Hurtling should not be labeled simply “free verse,” a category much too broad – there are countless ways to write non-metrical, non-rhyming poems – and misleading since “free” implies a lack of pattern. Witte resists the fallacious opposition between “formal” and “organic” poetry, preferring instead what he calls “organic formalism” to describe how his poems in The Hurtling take shape. While he does not use sonnets or received forms, all of the poems in The Hurtling conform to the same pattern: unrhymed, unpunctuated tercets, each one beginning with a very short line, followed by a medium length line, followed by a very long line. The lack of punctuation, heavy enjambment, and increasing line lengths have a simultaneously accelerating and restraining effect, as in the first two tercets of the opening ars poetica, “The Soloist,” about a performance by violinist Itzhak Perlman as witnessed from the front row of the concert hall:

This close

his lips pursed we could tell

how the slow opening phrase rose and broke through him his face

clogged his bow

arm rising and rowing how the music

eddied how he labored bearing the weight of memory and longing . . .

The image of the music “eddying” corresponds to the way Witte’s stanzas operate throughout the book. A river’s eddy, the recirculation of water behind a rock, flows in the opposite direction of the main course of the river, and Witte’s lines capture this tension, or movement in opposite directions. On the one hand, the mostly enjambed lines in each tercet accelerate as they accrue in length, culminating in the long line that “hurtles” across the page. On the other hand, this motion is suddenly stopped short after each long line, as the subsequent short line of the next stanza reins in the tempo. Furthermore, the lack of punctuation causes one to hurtle through the stanzas, but it also frequently hinders movement by creating, in conjunction with the line breaks, grammatical ambiguity that forces the reader to consider which way the language is directing us.

Through these tension-producing effects, along with the often violent diction and dissonant sound effects, Witte expresses the sometimes painful energy of contemporary life: “I’ve tried to invent a form that might capture the fleeting quality of our life, its acceleration and breathlessness. I’m trying to get from these triplets a formal sense of cohesion containing, under strain, the chaotic swerving of our experience.” —Scott Knickerbocker, The Kenyon Review